New Scientist Oct 27th 2018

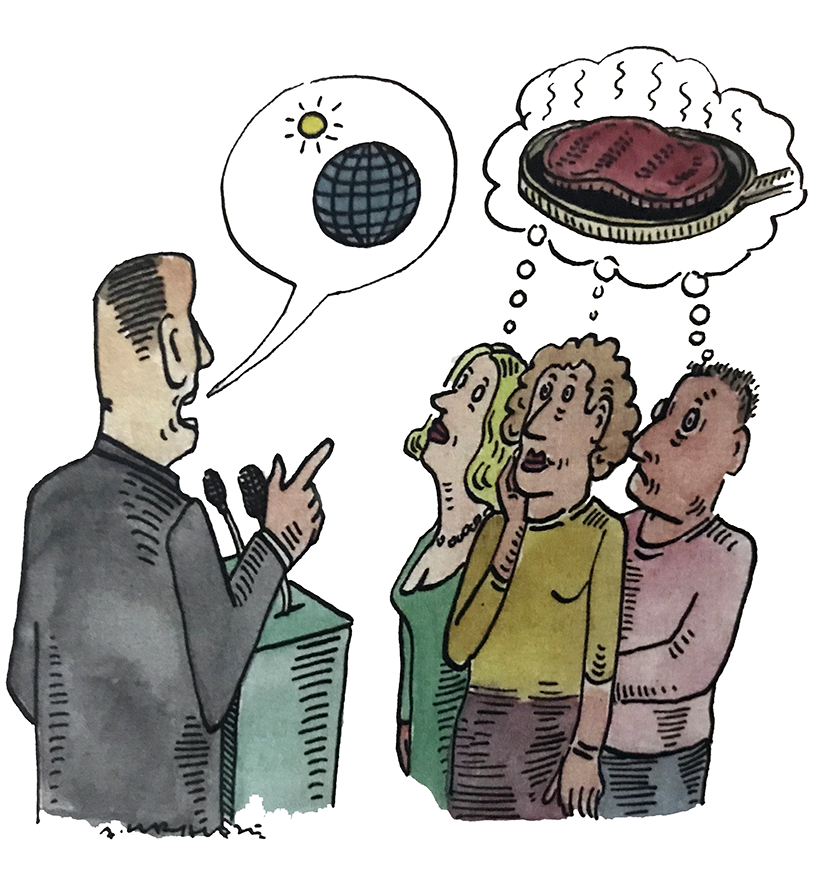

Shying away from the realities of climate change, such as the need to eat less meat, hinders our ability to tackle it, says Adam Corner.

If we’re to get climate change under control, the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report makes it clear that absolutely everything must be on the table. This includes lifestyle changes such as flying less and cutting down on eating red meat.

Yet Claire Perry, the minister in charge of the UK’s climate change strategy, doesn’t see it this way. She describes the idea of government telling us what to eat on climate change grounds as ‘the worst kind of nanny state ever’ adding: “Who would I be to sit there advising people in the country coming home after a hard day of work to not have steak and chips?”

Perry’s reluctance to ask us to change also says something important about why public engagement on climate change has not been straightforward. People in wealthy, industrialised nations such as the UK tend to see climate change as a ‘psychologically distant’ risk: not here, and not now. As a political issue, it struggles to compete with more immediate concerns like insecure employment or immigration.

Adding to the public’s sense of disconnect, warnings of apocalyptic futures have been paired with ‘simple and painless’ behavioural changes, like reusing plastic bags and banning straws. The research my colleagues and I do is designed to address these problems. One clear lesson from this research is that it is crucial to talk about climate change in the here and now, linking shifts in the weather to tangible and meaningful actions that people can take to cut carbon.

What’s more, most people find it easier to think about their own health than that of the planet, so emphasising the health benefits of low carbon activities like cycling instead of driving, or insulating draughty homes, might be a better way to go. Few of us discuss climate change with friends – perhaps that’s why many politicians underestimate concern on the topic, and the level of support for renewable energy. Getting the conversation going is the first step to meaningful action.

Most important of all is connecting with public values across the political spectrum. Avoiding wastefulness in energy use, improving health outcomes, conserving green spaces, creating a sense of pride in rebuilding energy infrastructure and fostering a sense of responsibility for future generations are all ways of talking about climate change that are more likely to resonate than guilt-laden messages about self-sacrifice.

Once the public is engaged in a meaningful conversation about our responsibility to consider how we eat, travel and live in a changing climate, skipping the steak and chips might not sound such a radical proposition.

Source: Adam Corner, research director at Climate Outreach, Europe’s leading climate change communication organisation.